The Changing Role of Women

Life for women in the 1900s was drastically different than it is today. Queen Victoria, ironically enough, brought the nearly exclusively man-run world into the 20th century and influenced the 1910’s even past her 1901 death. However, the average woman, though not theoretically seen as unimportant was considered less important than a man. Women were the weaker sex, needed protection, and were fragile beings not capable of doing everything a man could. It was considered taboo for women to own a business, support herself, or attend college. After all, these endeavours threatened the male-orientated standards of the day. Married women lost the right to own property, couldn’t make legal contracts, and laws made it nearly impossible for a woman to end an abusive marriage ("January 1, 1900"). While women could actually vote municipally in four provinces, they were prohibited from voting provincially or federally, and could not run for office.

At the turn of the century, women were slowly emerging from homebound producers to wage-earning consumers. Yet, despite the rise of women's importance on the economic, social, and political scene, many men still did not view them as strong, productive, or politically active members of society. Women were simply not valued the same as men. In fact, it was only in 1909, that the Criminal Code was amended to outlaw the abduction of women (Harvey). Before this, unless a woman was under 16 or an heiress, the abduction of any woman was legal. Even more surprising, the maximum penalty for stealing a cow carried a much stiffer penalty than that given for kidnapping an heiress (Harvey)!

During this decade, women wore their hair up in neat little buns and were not allowed to drink or smoke. In fact, in many places, they could be arrested for smoking in public. Most women wore corsets and other painful disfiguring garments to present a slender appearance. And yet, while the women of the 1900’s faced many restrictions, some monumental events in the slow “freeing” of the fairer gender still occurred. Helen Keller was the first blind/deaf woman to enter and graduate from college ("Decade by Decade: 1900s"). The Women’s Trade Union League was founded to help working women organize in 1903 ("January 1, 1900"). International Women’s Day was celebrated for the first time in 1908, and many reformers became historical figures of great significance, such as Jane Adams ("Decade by Decade: 1900s").

In the family, in most cases, the women stayed at home as mothers and housewives while the men made the family income. Women were expected to prepare all the meals on time, keep the house spotless, have and raise children, be “ladylike” and charming at all times, keep out of “male business” and magazines, always be properly dressed and proper in general, and please her husband and his guests. A woman’s place was in the home…and that was that.

For women to work outside the home, it had to be out of sheer necessity in the 1900’s, not as a privilege or a right. Of the mere 13% of women in the workforce, many suffered miserably in crowded factories and mills with unfair wages and conditions ("January 1, 1900"). The more fortunate were teachers, nurses, typists/secretaries, and sales clerks. Yet, even as early as the 1900's, some women were entering traditional male careers such as law, medicine, and science, with some women practicing medicine and law in Canada. While so many married women barely left the house, this new breed of women left the house for work and leisure. With this new independence, these women began to explore activeness in society.

The suffragette movement was spreading and growing in the 1910s. However, with the beginning of the Great War, in 1914, women around the world put on hold their campaigns for womens' rights in order to help the war effort. The mass recruitment of men was actually damaging the war effort - by spring 1915, the supply of shells to the front was running short. It became clear that there were two options: either men from the front would have to return to make ammunition instead of firing it, or women would have to take over their roles. In the early months, working-class women only worked 'suitable' trades, such as shoemaking, baking, and printing. However, with the labor shortage, women were soon being employed in industrial jobs previously regarded as the preserve of skilled artisans (The British Homefront, 3). By 1917 there were 35 000 women employed in munitions factories in Ontario and Montréal (The Canadian Encyclopedia). However, filling shells in munition factories was one of the worst jobs during the war. The women in the factories were nicknamed canaries, because the repeated exposure to TNT turned their faces yellow. The pay was good, but the health risks were abominable. Canaries suffered from skin and lung diseases, and women frequently were blinded or lost fingers while handling the explosives. In 1917 a fire broke out in a high-explosives factory at Silvertown, in east London, England. The resulting explosion was heard 50 miles away in Cambridge and 69 people in the factory and on the adjoining streets were killed instantly. Almost a thousand more were injured, 98 of them seriously (BBC, 2). Despite the tragedies, this change in women's work brought unexpected benefits. Their wages increased during the war years, they never equalled men's; in the munitions factories women's wages were 50-80% of those paid men, but suddenly women ceased to see themselves as fragile social ornaments . They no longer felt the need to male company while dining out - business girls ate out alone, or with each other, smoked cigarettes in public, and wore makeup. Clothes became more practical, and some young women - especially those working in factories or fields - took to wearing trousers. When the Great War finally came to an end on November 11, 1918, 12 million people had died. A Women's War Conference was called in 1918 by the federal government to discuss the continuing role of women, who took the opportunity to raise a number of political issues, including suffrage. Despite being put on hold due to the Great War, in 1916 Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta had given women the provincial vote; Ontario and BC followed in 1917. On 24 May 1918 the Parliament of Canada bestowed the federal franchise on women (The Canadian Encyclopedia).

The “roaring twenties” or “golden years” were fascinating times! It was a time of liberation and rebellion for women across the globe. Once the war was over, they were once again demanding women's rights, although this time, it was for different reasons. They mainly wanted the right to work in certain fields and work place and wanted to be legally categorized as "persons" (Simon, Amici, and Jamie Huang). After WWI, some women chose to stay in the workforce even though the men were coming back to their old jobs. They were still secretaries, teachers, nurses, and seamstresses like they were pre-war, but many decided to remain doing the jobs they did during the war. Now that they were not as needed, educated women were encouraged to stick to “nurturing” type jobs such as social work, nursing, teaching, and pediatrics. Many also worked in factories in the garment industry. Now despite how it sounds like women completely went back to their own ways, the 1920's were an era of firsts for many things, from the first shorts and fitted bathing suits worn by women, to the present idea of dating. There were also political achievements. In 1921, Agnes MacPhail was the first woman to be elected as a federal member ("Decade by Decade: 1920s"). Also, through the Persons Case, women in Canada became eligible for senatorial appointment in 1929 ("The Women's Timeline"). Women such as Emily Carr and Mazo de la Roche became very successful in the arts of painting and writing respectively ("The Women's Timeline"). Women gained the right to vote in the US and the National American Woman Suffrage Association became the League of Women Voters ("Decade by Decade: 1920s"). However a thing to remember is that, in Canada, Aboriginal and Asian women were excluded from those who got the right to vote.

During this time, there was a huge social rebellion with the emergence of the flapper. Flappers were mostly young women, and they lived as examples that women had the freedom and right to enjoy everything that a man did. Sleeveless dresses appeared, necklines dropped, and hem lines rose above the knee. The typical flapper was a young woman who danced provocatively, drank, wore heavy makeup, and dated freely. They had short flowy dresses, short hair, loved hats, and wore beads, sequins, and peacock feathers. It may not seem like such a big deal, but these women also smoked! Smoking often was not allowed in public where women were concerned. It was considered sinful and unladylike. The media eventually jumped in the bandwagon and actually encouraged weight-conscious flappers to smoke instead of eat sweets (Simon, Amici, and Jamie Huang). It was addicting enjoyable, without the added calories. Women during the time also began to ride bicycles, drive cars, and openly drink alcohol (in contrast to those in the Women’s Christian Temperance Union). The older generation was shocked! Sleeveless dresses appeared, necklines dropped, hem lines rose to the knee, the scandalous Charleston being popular, and long hair was bobbed. Forget corsets! Undergarments allowed more movement and comfort with the ability to be more involved in dance and sports and bathing suits became form flattering, practical, and colourful.

As we leave the twenties, women are earning 39% of US college degrees, they can compete in Olympic field events, women’s baseball is popular, women are questioning their rights on whether they have children or not, and they supposedly gain equal rights ("Decade by Decade: 1920s"). And as we look back, we can see that it certainly was a time of change.

During this time, there was a huge social rebellion with the emergence of the flapper. Flappers were mostly young women, and they lived as examples that women had the freedom and right to enjoy everything that a man did. Sleeveless dresses appeared, necklines dropped, and hem lines rose above the knee. The typical flapper was a young woman who danced provocatively, drank, wore heavy makeup, and dated freely. They had short flowy dresses, short hair, loved hats, and wore beads, sequins, and peacock feathers. It may not seem like such a big deal, but these women also smoked! Smoking often was not allowed in public where women were concerned. It was considered sinful and unladylike. The media eventually jumped in the bandwagon and actually encouraged weight-conscious flappers to smoke instead of eat sweets (Simon, Amici, and Jamie Huang). It was addicting enjoyable, without the added calories. Women during the time also began to ride bicycles, drive cars, and openly drink alcohol (in contrast to those in the Women’s Christian Temperance Union). The older generation was shocked! Sleeveless dresses appeared, necklines dropped, hem lines rose to the knee, the scandalous Charleston being popular, and long hair was bobbed. Forget corsets! Undergarments allowed more movement and comfort with the ability to be more involved in dance and sports and bathing suits became form flattering, practical, and colourful.

As we leave the twenties, women are earning 39% of US college degrees, they can compete in Olympic field events, women’s baseball is popular, women are questioning their rights on whether they have children or not, and they supposedly gain equal rights ("Decade by Decade: 1920s"). And as we look back, we can see that it certainly was a time of change.

By 1930, women were entering universities in large numbers; 23% of all undergraduates and 35% of all graduate students were female. The Great Depression reversed this trend and in the 1930s many women were forced back into domestic service. Canadian federal employment figures show that even in the garment industry - a longtime employer of women - they were being laid off at a higher rate than men (The Canadian Encyclopedia). The Great Depression of the 'threadbare Thirties' was taking its toll. It left millions of Canadians unemployed, hungry and often homeless. Due to Canada’s heavy dependence on raw material and farm exports, combined with a crippling Prairies drought, few countries felt the effects of the depression as much as Canada. Between 1929 and 1933 the country’s Gross National Expenditure (overall public and private spending) fell by 42%. By 1933, 30% of the labour force was out of work, and one in five Canadians had become dependent upon government relief for survival (The Canadian Encyclopedia). Despite the horrific poverty of the Depression, the 1930s was a decade of firsts for women. In 1931, Jane Addams became the first woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize for her work with the poor in Chicago. Amelia Earhart was the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean in 1932. On 6 March 1933, two days after becoming First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt held what was to become the first of 348 press conferences, with about 35 women in attendance. The idea emerged from her flourishing friendship with reporter Lorena Hickok as a direct measure to help women reporters keep their jobs during the depression. In these conferences, Mrs. Roosevelt informed the American people of news, whether it was the threat that Hitler presented to Europe or of her own life in the White House. The conferences were a unique situation, as they were banned to all men. This was a direct measure to help women reporters keep their jobs during the depression, as it required the publication companies that wanted to carry the news which Mrs. Roosevelt generated to continue to employ women reporters (First Ladies). Previous to this, women reporters in Washington were confined to coverage of “style” issues, such as clothes and entertaining.

Just as the world was climbing back to its feet, disaster struck once again with the commencement of World War II, when Germany attacked Poland on September 1, 1939.

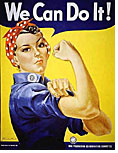

Women of the forties were vital in the war effort. For the ladies, WWII mirrored WWI in many ways. WWII erupted and women were again to dutifully take over all the jobs left behind. As Canada entered WWII there was a high rate of unemployment, but by 1942, there was a labour shortage and everyone was needed to help out. A federal National Selective Service program was implemented to recruit single women for employment, but soon came to recruit married, childless women, and eventually married women with children when the labour shortage continued ("Women at Work"). Propaganda was created to lure women into the work force. “Rosie the Riveter” – a fictional character depicting the “ideal” woman worker – was created. The character was an instant media success, and the “Rosie the Riveter” song came out in 1942 ("Women at Work").

Working women were the country’s safety net! They filled the jobs of men, did anything and everything, supported both their families and themselves, and did all of this, while facing harassment from men ("Women at Work"). One issue was childcare, and daycares were soon opened. The main obstacle, however, was changing men’s attitudes. Working was not new to women, and everyone – including the men – agreed that workers were greatly needed, but they also agreed that it would only be temporary. Male employees were suspicious of women; women’s needs were secondary to men’s; and positions of power were denied to them ("Women at Work"). As time went on, these attitudes drastically changed and employers eventually praised them. But, as soon as the war was over women were encouraged to leave work to make way for returning soldiers. Many were laid off or cut back into lower paying “female” jobs. The majority of women returned to the home, but the idea of married women working stayed with women everywhere, and married women soon became fixed members of the working world.

Outside of the war effort, there were many other achievements. Québec women were able to practice law, and high jumper Alice Coachman became the first African American woman to win an Olympic gold medal ("The Women's Timeline"). Chinese and Japanese women – and men – obtained the right to vote, and Canadian women no longer lost their citizenship automatically if they married non-Canadians ("The Women's Timeline"). Women’s clothing of the forties was typically modeled after the utility clothes produced during war rationing. Tailored suits, square shoulders, narrow hips, and skirts that ended just below the knee were the height of fashion. After the war, it was back to a more feminine style, but most excitedly – during the war – slacks first gained popularity!

Working women were the country’s safety net! They filled the jobs of men, did anything and everything, supported both their families and themselves, and did all of this, while facing harassment from men ("Women at Work"). One issue was childcare, and daycares were soon opened. The main obstacle, however, was changing men’s attitudes. Working was not new to women, and everyone – including the men – agreed that workers were greatly needed, but they also agreed that it would only be temporary. Male employees were suspicious of women; women’s needs were secondary to men’s; and positions of power were denied to them ("Women at Work"). As time went on, these attitudes drastically changed and employers eventually praised them. But, as soon as the war was over women were encouraged to leave work to make way for returning soldiers. Many were laid off or cut back into lower paying “female” jobs. The majority of women returned to the home, but the idea of married women working stayed with women everywhere, and married women soon became fixed members of the working world.

Outside of the war effort, there were many other achievements. Québec women were able to practice law, and high jumper Alice Coachman became the first African American woman to win an Olympic gold medal ("The Women's Timeline"). Chinese and Japanese women – and men – obtained the right to vote, and Canadian women no longer lost their citizenship automatically if they married non-Canadians ("The Women's Timeline"). Women’s clothing of the forties was typically modeled after the utility clothes produced during war rationing. Tailored suits, square shoulders, narrow hips, and skirts that ended just below the knee were the height of fashion. After the war, it was back to a more feminine style, but most excitedly – during the war – slacks first gained popularity!

With war rations being abolished, the modern supermarket making its appearance, the television popularizing, and the coronation of a new the Queen (Elizabeth II), the 1950s was a time of relatively peaceful change. After WWII, women were, as in the case of WWI, expected to return to the home, and many did, but, again, many did not. In England, one in five married women went to work in 1951; by 1957 the figure was one in three (Porter). There was a dramatic increase in birth rates, and new housing was impacting the landscape. The development of better cars in the 50's led to the birth of the 'commuter age', with the first suburbs beginning to emerge. New sets of values appeared; there was pressure to “maintain appearances” within your town, so more families attended church, community social functions, etc. On average, mothers did 99 hours of housework each week. With an increase in televisions, the entertainment industry was booming, and TV dramas and comedies, like Father Knows Best and Leave It To Beaver re-enforced the idea of a nuclear family and gender stereotypes. After WWII, technology started changing the way beauty was perceived: bathrooms with electric lights and mirrors highlighted concerns about acne and formerly overlooked details (Porter). Actress Marilyn Monroe was perceived as the epitome of beauty in the 50s. The pressure to live up the ideal was tough and demanding, similar to today’s pressure of the ‘slim ideal’. In the words of The Happy Home (a book published by the Good Housekeeping Institute), "Your choice of clothes and the way you wear them, your walk, your hairstyle, hands and makeup - all these tell what kind of woman you are.

However, not all was peaceful as the Soviet Union and the United States faced off in the Cold War, that had started in 1945 and would continue until 1991.

"Everywhere are evidences of the continuous underground, cancerous movements of Communism ... Only eternal vigilance can protect us against Communism and its infiltration into our way of life." - Canadair advertisement, 1955

It was a decade of extremes, in the 1960s. From transformational changes to peculiar contrasts, this decade was marked by everything from flower power to rebellion, to backlash. More females than ever entered the paid workforce. With this, women’s dissatisfaction regarding the huge discrepancies in pay and advancement between the genders as well as workplace sexual harassment grew (Napikoski). Yet, even with this strong presence, women still only earned 60% of the earnings of a man ("Decade by Decade: 1960s"). During the radical 60’s, it was no longer surprising to see women leaders in former “men-only” fields such as television (Marlo Thomas starring in That Girl) and the Supreme Court (Justices Sandra Day O'Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg) (Napikoski).

In 1960, the federal government approved a birth control pill and by the end of the sixties, over 80% of wives of childbearing age were using contraception (Murray). People sat on both sides of this moral issue, but regardless, most women revelled in this new-found personal freedom. Of course, pop culture reflected the tumultuous times with such gender opinionated hits such as Lesley Gore's song, “You Don't Own Me” ("The Women's Timeline").

Early on, women’s fashion trends were Jacqueline Kennedy influenced with elegant pillbox hats, stiletto heels, pastel suits, and full skirted gowns with low necklines and formfitting waists. However, in terms of memorable fashion, the end of this decade is owned by the hippies. Influenced by the Vietnam War, the hippie style emerged with frayed, bell-bottomed jeans, tie-dyed shirts, headbands, fringed buckskin vests, bare feet or sandals, and braless women ("Fashion 1960-1969"). It is often heard that there were “bra-burnings”, but that is a myth. Women actually created “freedom trash cans” where they threw away bras, girdles, hair curlers, dirty magazines, and anything else that they felt symbolized them as beauty/sex objects ("The Women’s Movement 1960-1973"). Feminists continued their fight against these dehumanizing ideals by protesting at the 1968 Miss America contest arguing that the pageant was sexist (especially the swimsuit portion) ("The Women’s Movement 1960-1973").

Betty Friedan’s, 1963 The Feminine Mystique, described women’s frustration over being expected to find fulfillment through the achievements of their husbands and children ("Decade by Decade: 1960s"). In 1966, the National Organization for Women was formed which sought equality for women in all areas of life (Napikoski). However, the NOW failed to include minority groups and working class women. Politically, a very exciting moment in 1960 occurred when Aboriginal women (and men) gained the right to vote ("Decade by Decade: 1960s")! In the US, the 1963 Equal Pay Act and the 1964 Civil Rights Act (which forbid discrimination based on sex) were signed into law (Napikoski).

To be a young woman in the late sixties and early seventies was unimaginably exciting. It was yet another time where women were pioneers. On the space frontier, Valentina Tereshkova made history as the first woman in outer space ("The Women's Timeline"). A team of 13 women were also secretly trained as astronauts by NASA along with 7 men ("The Women’s Movement 1960-1973"). Unfortunately, the program, called “Mercury 13”, was abandoned as it lacked political support. Other interesting women during this time were: Shirley Chisholm (the first African-American woman elected into the U.S. House of Representatives), Eleanor Roosevelt (a former first lady who chaired President John F. Kennedy Jr.’s Commission on the Status of Women), and Audrey Hepburn (one of the most beloved movie stars of her day who starred in classics from the 1960’s such as “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” and “My Fair Lady”) ("Decade by Decade: 1960s").

A woman is like a tea bag - you can't tell how strong she is until you put her in hot water.

~ Eleanor Roosevelt

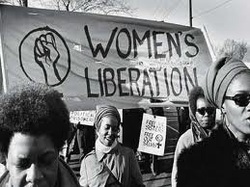

Known as the second wave of feminism, the 1970s marked a time of change for women around the world. On August 26, 1970 - the 50th anniversary of women's rights in the US - a nationwide demonstration for women’s rights, The Women’s Strike for Equality, was held. It was described by Time magazine as “the first big demonstration of the Women's Liberation movement.” It was organized by the National Organization for Women (NOW) and its then-president Betty Friedan. At a NOW conference in March 1970, Betty Friedan called for the Strike for Equality, asking for women to stop working for a day to draw attention to the prevalent problem of unequal pay for women's work. She organized the protest, using such slogans as "Don't Iron While the Strike is Hot!" (Napikoski, 2). Women were greatly influenced by books and articles by feminists such as Kate Millett, Germaine Greer, Gloria Steinem and Shulamith Firestone, and by publications such as Women Unite: An Anthology of the Women's Movement (1972) and Margaret Anderson's Mother Was Not a Person (1973).

In the late 60s and 70s Canadian women from Vancouver to Halifax began forming groups. Organized in 1968, The Vancouver Women's Caucus published The Pedestal from 1969 to 1973. In 1969, the Montréal Women's Liberation Movement was founded, the Front de libération des femmes du Québec published a feminist manifesto in 1970, and the Centre des femmes edited the first French-language radical feminist periodical, Québécoises deboutte! (1971-75). In the beginning, most were awareness groups, but many quickly turned to concrete action (The Canadian Encyclopedia, 4). They began providing abortion services, health centres, feminist magazines, militant theatre, day-care, shelters for battered women and rape crisis centres, and organizing for equal pay. In the early 1970s, the movement consisted of smaller radical groups, but the movement steadily expanded to incorporate women of diverse opinions and from all parts of Canadian society, including welfare mothers, professional, business and executive women, native women and immigrant domestic workers.

It's more about changing the recipe of the cake than getting an equal slice.

-Kate Millett, 1971

Throughout the eighties, women all over the globe were still the main managers of the home, but there was a noticeable change…many men were right behind them with the laundry basket. The term “women’s work” was referred to less and less, and the proportion of couples in which women were the primary breadwinners rose to 3 in 10 ("Gender Roles around the House"). In this decade, men finally understood that their contributions to completing domestic chores directly influence their wives’ emotional health – a radical idea ("Gender Roles around the House")! Some men even began to be the stay-at-home parent and to take paternity leave.

Shoulder pads were all the rage. Everything from the brassier upwards came with its own set and, by the end of the decade, some were the size of dinner plates! In fact, they defined fashion of the era. This now-ridiculed style trend was called “power dressing”, and people felt it gave the wearer a look of high status and position ("Women's Clothing"). The 1980’s would continue as all others before and after it with all aspects of pop culture (i.e. music, fashion, literature etc.) reflecting the attitudes, political agendas, and belief systems of the time.

Abortion was also at the forefront of this decade. Illegal and self-abortions were exceedingly common ("The Women's Timeline"). Some US states allowed abortion under certain circumstances, and it was – and still is – a political and moral hotbed. Feminists opposed so many restrictions to and the high prices of abortions ("The Women's Timeline"). Most religious groups, however, wanted it banned. Doctors and facilities providing abortions were subjected to picketing, chemical attacks, death threats, invasions, and blockades ("The Women's Timeline"). Feminists argued that it’s a women’s “right” to dictate what happens to her own body while opponents desperately fought for the one with no voice—the unborn child.

Naturally, many political landmarks concerning women’s rights and violence against women characterized the time. In 1981, courageous women – concerned about women's rights being excluded from the proposed new Charter of Rights - lobbied Members of Parliament, and consequently women's rights were included in Canada's constitution (Morris). No longer could bars and pubs refuse service to women. In 1982, NDP MP Margaret Mitchell was ridiculed after raising the issue of violence against women in the House of Commons. The outcry resulting was so fierce that in 1983, rape laws were broadened to sexual assault laws (Morris). Finally, it became a criminal offence for a man to rape his wife, and charges were laid in several domestic violence cases. Other monumental shifts also occurred. Women were now allowed to apply for loans and credit in their own names, retire at the same age as men, work night shifts in factories, and Aboriginal women who married non-status men were no longer forced to give up their “Indian” status (Morris).

Not surprisingly, many amazing women emerged in the eighties. Sharon Wood, from Alberta, was the first Canadian woman to reach the summit of Mount Everest (Morris). Christa McAuliffe, along with seven others, trained to be one of the first civilians to go into space ("The Women's Timeline"). Sadly, this historical event was shrouded in devastation when the space shuttle Challenger exploded while the world watched, horrified. Tina Turner’s brand of rock exploded the charts as did the newly-discovered Madonna’s pop. Karen Carpenter died from complications related to an eating disorder, bringing awareness to the plight of anorexia (Morris). The Oprah Winfrey Show aired nationwide, turning Oprah into one of the most admired and watched talk show hosts in the country. And ironically…Wonder Woman becomes as popular as ever!

By the mid-1990s, the generation who had grown up with the women’s movement of the 1960s and '70s had come of age, starting families and careers of their own. It's not surprising then, that the third wave of feminism was in this decade. Some early advocates of the new approach were literally daughters of the second wave. Third Wave Direct Action Corporation (organized in 1992), which became the Third Wave Foundation in 1997, was dedicated to supporting “groups and individuals working towards gender, racial, economic, and social justice” (Encyclopedia Britannica, 2). Both were founded by (among others) Rebecca Walker, the daughter of the novelist and second-waver Alice Walker. Walker, and others like her grew up with the expectation of achievement and examples of female success, as well as an awareness of the barriers presented by sexism, racism, and classism. Third-wave feminists sought to question, reclaim, and redefine the ideas, words, and media that have transmitted ideas about womanhood, gender, beauty, sexuality, femininity, and masculinity, among other things (Encyclopedia Britannica, 3). There was a distinct shift in perceptions of gender, with the concept that there are some characteristics that are strictly male and others that are strictly female giving way to the notion of a gender continuum. From this perspective each person is seen as possessing, expressing, and suppressing the full range of traits that had previously been associated with one gender or the other. Media was a major factor in 1990s feminism. In the movie-world, teen girl audiences emerged as one of the most powerful demographic factors of the 90s, often creating surprise hits out of movies, such as the low-budget romantic comedy Clueless (1995) and the slasher parody Scream (1996). In 1997, teen girls saved the romantic epic Titanic from financial disaster when groups of them flocked to theatres for repeat viewings of it. In music, phrases such as "Girl Power" moved into the mainstream with the international, if short-lived, phenomenon of the Spice Girls, adored by very young girls. "By sheer bulk," according to one studio executive, "young girls are driving cultural tastes now. They're amazing consumers." (Karlyn, 2) For the first time, girls controlled enough money to attract attention as a demographic group. Media programming for children increasingly depicted smart, independent girls and women in lead roles, including Disney heroines such as Belle (Beauty and the Beast, 1991), and Mulan (1998).

It’s clear that the role of women today is in vast contrast to the woman of the 1900’s—thankfully. More and more, women are defining their roles, not having their roles dictated to them. It’s a freedom that has been slowly and painfully discovered. This hundred year study clearly revealed the emancipation of women for what it is: fascinating and humbling. Courage, strength, determination, solidarity, and endurance changed the role of women forever. It shows just how far we have come, and how far we still have to go.